Factors like current market conditions, rising equipment costs, a lack of skilled workers, geopolitical tensions, and the slow rollout of government grants are causing delays in the construction of many planned fabs.

Across the industry, stakeholders are grappling with the challenge of aligning production with evolving market demands. Many chipmakers are planning new semiconductor fabrication plants, or fabs, to increase their production capacity—often with the help of government funding. But things aren’t going exactly as planned.

The Race for New Fabs

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted some of the biggest vulnerabilities in the global semiconductor supply chain. Chip shortages and transport bottlenecks made companies realize they could no longer depend on a single location for chip supply. The Russian war in Ukraine has further underscored the dangers of relying on a small number of chipmakers, many of them in politically volatile regions. This has encouraged a mindset shift across the industry. Manufacturers are considering moving some of their factories to different regions, and OEMs are working to geographically diversify their supply chains. Meanwhile, several governments have started incentivizing the growth of onshore chip manufacturing in an attempt to prepare for future market disruptions.

Rapid post-pandemic growth in many industries has driven a surge of demand for chips, which has sparked many chipmakers to consider expanding—and government funding seems poised to make this easier than ever. The CHIPS Act set aside over $50 billion in R&D funding, tax credits, and new fab grants to bolster semiconductor manufacturing in the US. Japan and the European Union have passed similar measures, and India has launched an ambitious project to become a global semiconductor hub.

As a result, companies are announcing new fabs left and right. At least 70 new projects are in the works in the US alone, including from industry leaders Intel and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Infineon is working on a $5 billion fab in Germany, and Samsung has plans to invest $230 billion in a handful of new fabs in South Korea. But planning and funding new fabs is the easy part—getting them up and running is another matter. There are many factors contributing to the recent series of new fab delays.

What are the challenges of building new semiconductor fabs?

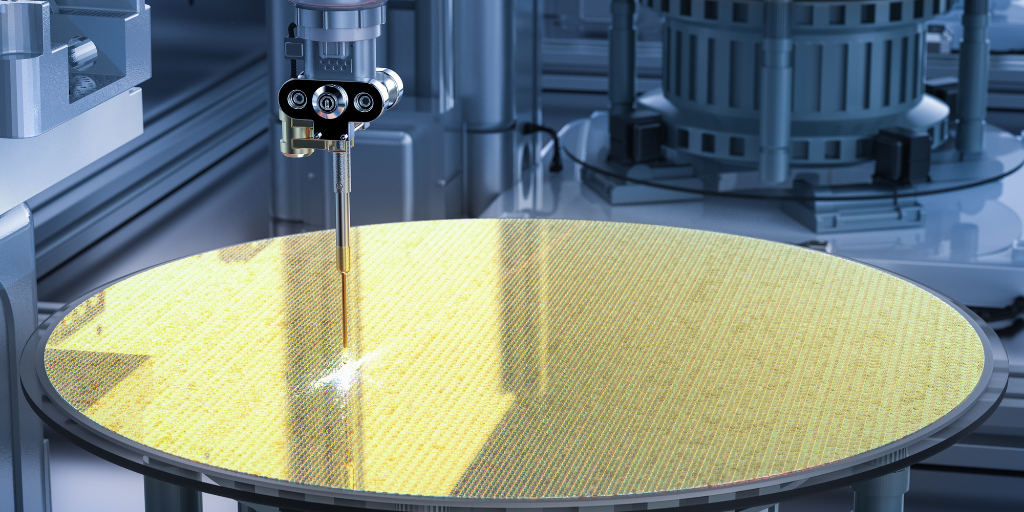

Fabs are large, complex buildings that can manufacture millions of chips every hour. They require huge air handling facilities to maintain the stringent temperature, humidity, and cleanliness standards necessary for chip manufacturing. They also require hundreds of advanced tools and machines, some costing millions of dollars themselves. Building a fab, then, is no easy feat—it typically takes 18 to 24 months to get a fab fully up and running, and that’s if everything goes smoothly.

But in today’s climate, new fabs face several challenges that threaten to delay the industry’s efforts at growth. For one thing, the government funding that many new fabs rely on has been slow to materialize. Though the CHIPS Act was passed in July 2022, it wasn’t until December 2023 that the first grant—$35 million to BAE Systems—was awarded. Larger awards to major players like TSMC, Intel, Samsung, and Micron are slated for later this year, but for now, these companies are still locked in negotiations with the government.

Another factor is market conditions. After a prolonged shortage, many chip types are seeing a slump in demand right now. Companies that made ambitious expansion plans a few years ago, when chips were in short supply, are suddenly dealing with excess inventory and little spare cash for new fabs. US manufacturer Microchip applied for CHIPS funding two years ago, when the company was struggling to keep pace with its orders, and was approved for $162 million. But sales have since declined so much that the company recently had to shut down two of its factories for two weeks. Microchip says it still plans to use its CHIPS funding, when it arrives, to upgrade some of its facilities—but it will have to postpone other projects until business improves.

Some chipmakers are continuing with their expansion plans, basing new fabs on projected future demand rather than current demand. But these companies are running into other challenges, like the rising cost of equipment and lack of skilled workers. Take TSMC, which is in the process of building two factories in Arizona. In 2023, the company announced that both fabs would be delayed at least another year, citing the slow rollout of federal funding and local workers’ lack of expertise in installing sophisticated equipment. Intel also postponed their new $20 billion Ohio plant, which now isn’t slated to go live until 2026, due to a combination of slow market conditions and uncertainty over federal funding.

What do fab delays mean for the market?

Although chipmakers are racing to build new fabs, recent delays mean it will be a few years before the market sees the fruits of these labors. With explosive growth projected in many industries, companies that continue with expansion plans in today’s sluggish market will be glad they did. The upcoming flood of federal funding should help chipmakers prepare for the future, so that when demand picks up again, production capacity will be able to keep pace.

However, it’s important to keep in mind that most new fabs are designed for building high-tech, next-generation chips — not legacy products. High-reliability industries like automotive and defense & aerospace still depend on legacy chips and have been reluctant to transition to newer, unproven chips. Even when today’s new fabs come online, these industries will likely still face shortages. To combat this, companies should invest in building resilient supply chains, find creative ways to source legacy parts, and transition to advanced chips when possible.

Read more: